POSTS

What's the Hurry?

Analytics is taking over football. That much I am sure about. This means we can expect new, innovative ways to coach and manage teams going forward. Panthers owner David Tepper has spoken about being innovative in his approach to filling the head coach role, but also his front office staff. Even ex-GB coach Mike McCarthy has re-branded himself as analytically-minded in hopes of getting a job in 2020. Part of the many, many benefits of analytics taking over football is the ability for teams to optimize play calling and game planning strategies. They can do this by looking deeper at play-by-play data.

It doesn’t take a PhD to know that a team runs the ball more than other teams. Every coach should know the other team’s tendencies for 3rd down. These metrics have been tracked heavily for many years. The new age of analytics allows for more granular splits and for us to look deeper at what is being called in-game. In this post, I examine the use of no-huddle offenses over the years. Even this has been tracked for a while now by analytic firms (and I hope teams), but with the use of NFLScrapR’s expected points added (EPA), we can look at how efficient no-huddle has been and when teams should use it.

I want to make a couple assumptions before I start ranting. First of all, the term “no-huddle” does not mean a hurry-up offense. It is simply as it suggests - the offensive team calls the play without huddling at the line of scrimmage (or sometimes in the previous huddle.) It can be quick-paced or time consuming, so keep that in mind here. Second, all analysis was done using what I am referring to as “game-neutral” plays and outside the 2-minute warnings. This means that the win-probability does not exceed 80% for either team. I do this so that I can isolate how often teams use no-huddle in their normal game plan, when the game is still in reach and there is time left on the clock.

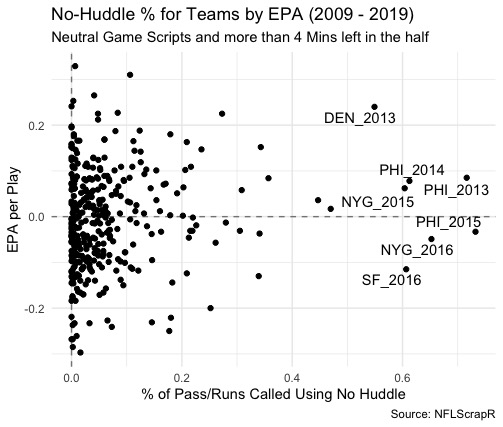

For the most part, not many teams use no-huddle in the game. The sharp increase in 2014-2016 can be largely explained by a few outlier teams and coaches. Of the top 7 teams to use it 50% or more of its snaps since 2009, 6 of them are from 2 coaches - Chip Kelly and Ben McAdoo. Not really a surprise there with Kelly’s tenure at the collegiate level. We also see Arizona’s use of no-huddle increase significantly with Kingsbury calling the offense. With those few teams aside, it is a little odd to see the amount of teams that do not use no-huddle.

When looking at the correlation of no-huddle % and EPA per play, there is not a significant relationship between the two, so why am I spending my few days off of work and school writing about this? Besides the fact that I have nothing better to do, there is more to this than just the amount of times no-huddle is run by a team. I want to see when a team should call no-huddle, if at all.

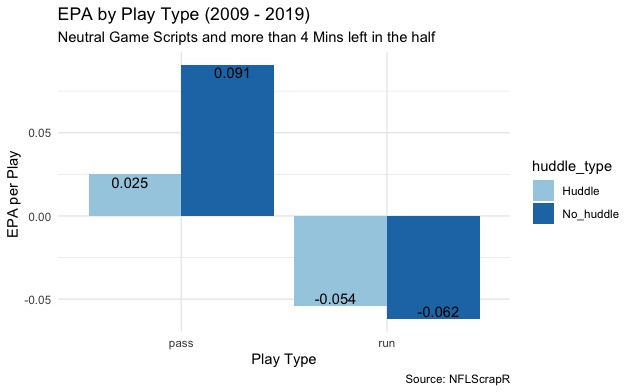

When we look at the split by play call, we see a drastic difference in EPA between no-huddle passes and passes called in the huddle. All else equal, no-huddle passes have been way more efficient. Running the ball seems to be much closer, and since running is not as efficient anyway, I look closer at passing splits from here on out.

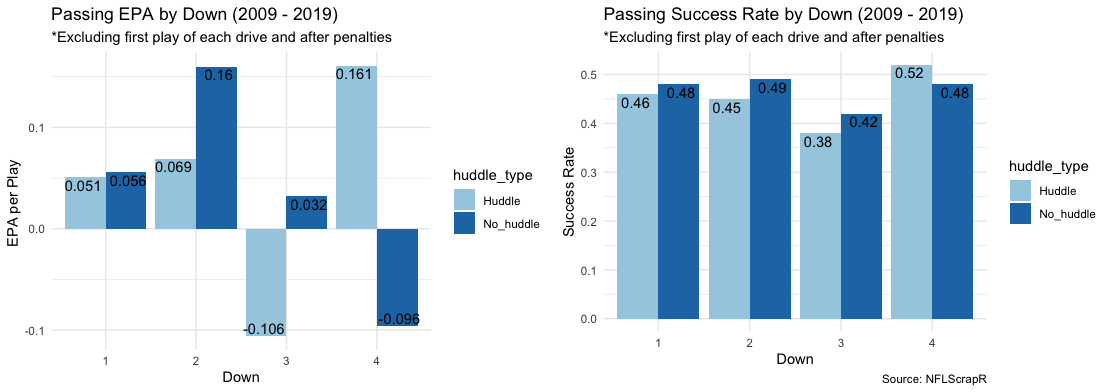

One aspect I wanted to look at was when teams should go no-huddle. Passing by down shows no-huddle passes are more effective on 2nd and 3rd down, while both situations are very similar on 1st down. Considering success rate (plays with positive EPA) is a smaller difference than EPA, one can conclude that passing plays in general are traditionally effective, no-huddle plays have a bigger impact in the game than those called in the huddle.

The true reasoning for the larger impact would need to be further analyzed, but I would guess this has a lot to do with personnel on the field. For example, defenses may come out in base personnel on first down and by doing no-huddle, the offense can dictate the substitution of the defense. By keeping a “run-first” defense on the field, the offense prevents better coverage and pass rush defenders from coming onto the field. Again, that is speculation and personnel data would be needed to back that up, but may provide some insight into why no-huddle is more effective.

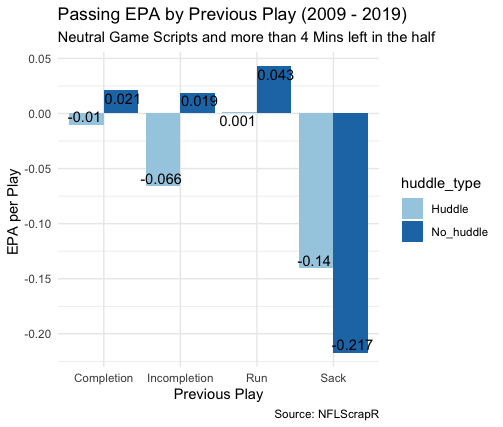

Another aspect of when team’s should go no-huddle is dependent on what the previous play outcome was. Again we see no-huddle more effective than huddling up for most outcomes. Sacks may be an unsurprising difference, but it is interesting that the biggest difference in EPA is for incompletions. I would’ve figured incompletions would be a good time to regroup, but the data says differently. Conversely, completions have a small difference, where the traditional thought of keeping momentum going would apply.

By looking at all this, it makes you wonder why teams don’t go no-huddle more often throughout the game. I’m not expecting every play to be no-huddle as players tire and different personnel packages are important, but it seems it would be beneficial to script series of plays throughout the game. Just like teams script plays to start a game, this is a way for teams to take advantage of effective play calling.

Taking this analysis further, I would like to look at using personnel data. Knowing what formation the defense and offense is would greatly shed light into these situations and allow for better game planning. It would also be interesting to model all these variables to see just how predictive they are when looking at successful play calling.